This beautiful collection of 19 Margaret Randall original photographs will be offered in a silent auction to benefit the SouthWest Organizing Project on June 8, 2007. They were taken by Randall in Nicaragua in 1979. She used a Pentax K-1000, rolling the film herself from the ends of Cuban newsreel, and printed on Agfa Potriga, a warm-toned semi matte paper. This page is composed of snapshots of the photographs. The originals are each 11x14 inches, stamped on the back and in great condition.

A young woman at

In 1979 I was living in

I remember how excited Grandal was when I told him my plans. “You can use the diplomatic pouch to send me your exposed film,” he suggested, “and I’ll develop and print the pictures for you here.” It was a kind offer, and generous, but I was incensed. Didn’t my mentor trust me to develop and print myself? I rejected his suggestion, and of course made many mistakes—learning as I went along. More than one photograph in this set of 19 can no longer be reproduced because of my faulty developing and fixing techniques. The negatives no longer exist.

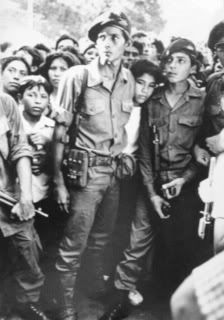

It is with a deep sadness and anger that I think back to that time in 1979 when the Sandinista revolution was new and hope was on everyone’s horizon. Nothing seemed impossible. Today it is devastating to think that men who have usurped the Sandinista dream are back in power, but without the intention of doing anything for their impoverished nation. These photographs bring back a flood of memories.

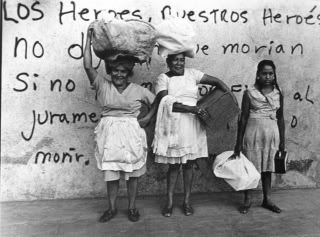

There was the day I spotted those lines from Leonel Rugama’s poem, jumped out of the jeep and raised my camera to capture the wall with the words “Los heroes, nuestros heroes, nunca dijeron que morían por la patria sino que murieron . . .” Three women carrying loads of wash walked into the picture plane, and turned and posed just as I snapped the shutter. Rugama had been a 20 year old seminary student when he was assassinated in 1967 by Somoza’s National Guard. Had he lived, he would have been one of his country’s finest poets. Many ordinary Nicaraguans know his poetry by heart.

The group of children crouched around the makeshift cross bearing the name "José" brings me back to the day I visited Doña Leandra in Estelí. She was a poor woman, who sold homemade sweets in theThe group of children crouched around the makeshift cross bearing the name “José” brings me back to the day I city market. I had asked her to help me trace the last hours of my friend José Benito Escobar’s life, and she took me to the spot where he’d been gunned down. José Benito and I had been friends in

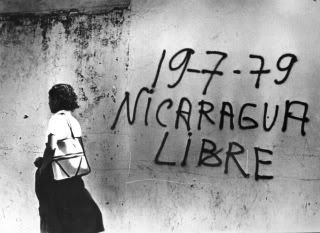

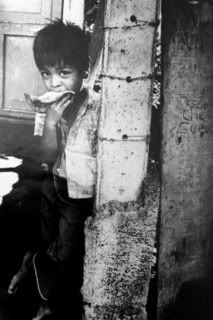

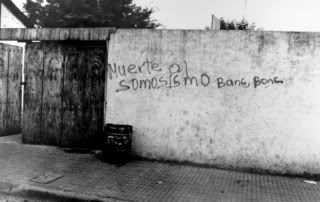

In several of these images one can see the writing on the walls: figuratively and also literally. Throughout the insurrectional period people often painted slogans on buildings and elsewhere, in memory of a fallen comrade, to encourage a difficult struggle, or as a promise of what liberation would be like.

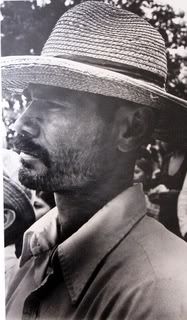

Two of the images were taken at the outdoor poetry reading honoring the birthday of

Another event brought back by these photographs is Carlos Fonseca’s funeral. Carlos was the undisputed leader of the Sandinistas, gunned down in the mountains in 1976. Until victory, a local peasant tended his grave. After victory, his body was moved to

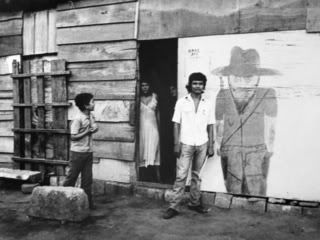

Perhaps my favorite of all these photographs is the one in which we see a house put together with scraps of wood and corrugated metal. A young man has painted the figure of a Sandinista fighter on the wall. He proudly shows us his handiwork, as his sister—a prostitute who can already envision a different kind of life—looks from the doorway. There is so much spontaneity in this image, and so much promise. I have often wondered what became of this family.

I don’t remember where I made the photograph of the broken doll lying in the earth of some roadside field. But although the precise place has vanished from my aging memory, I will never forget the feeling seeing that doll evoked, nor the act of pressing my camera’s shutter.

By the way, all these images were made with a Pentax K-1000, probably the cheapest 35mm. camera on the market at the time. I rolled my film myself, from the ends of Cuban newsreel given me by one of the filmmakers of the era. Today I note with a certain wistfulness the paper on which these pictures were printed: it was Agfa Potriga, a warm-toned semi matte that I used to love. I don’t think they make it anymore, and in any case—like most photographers—I’ve long-since gone digital.

I am so glad that